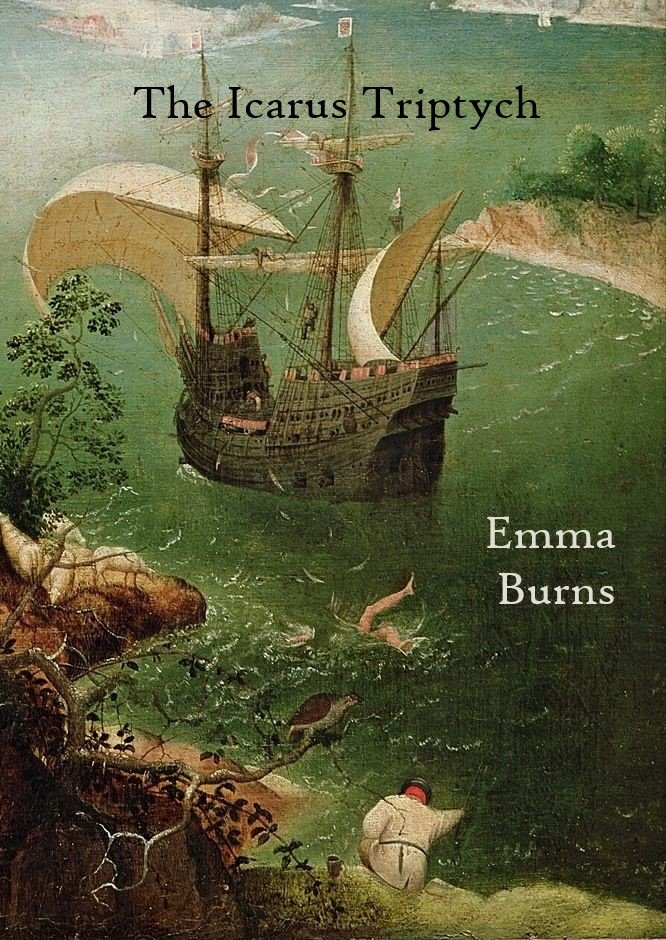

The Icarus Triptych

One day Alice looked at my portfolio again and sent me over to the set to paint a picture to hang on the wall, something that would match the walls and furnishings. She was crabby, something about artwork clearances that hadn’t gone through, or cost too much, or something, so I grabbed all the materials and ran, even though the folding easel was awkward and carrying a canvas and everything else together was like juggling weasels.

The guard let me in, and I found the room and set up my stuff. I looked around for inspiration as to what to paint and saw that someone was sleeping in an armchair in the room. That was so extremely not allowed that I almost wanted to wake him up, so Alice wouldn’t rip his head off. But he looked exhausted, so I didn’t. He was all speedy and trim like an athlete, like a runner, but tanned and stubbly and hot like a magazine model, with that clippered short hair only extremely good looking men can pull off—everyone else looks like a convict. I could immediately picture him bouncing a soccer ball on his foot or off his knee.

Instead of waking him up, I sketched him and then painted him. I always prefer painting people over things, and live models over anything else, though I’ll work from a photo in a pinch. He was sleeping in a deep blue armchair with a pattern of tiny yellow flowers and green vines and leaves. He was dressed in a soft lighter blue v-neck tee and dark jeans and was curled up in the chair like a little kid, with one fist up near his cheek.

I painted for maybe two hours and was filling in the background when I noticed with a start that he had woken up and was looking back at me. He seemed like he recognized me, or knew me, one of those long steady looks that went on much longer than I expected it to. I kept looking back at him, wondering whether I knew him from somewhere.

“Hi,” I said finally.

“Good morning,” he said. British accent, nice voice. He still hadn’t stopped staring at me.

“I’m almost done,” I said.

“All right,” he said peacefully. “Almost done doing what?”

“Alice sent me to paint something for this wall,” I said. “I didn’t want to wake you.”

He sat up and stretched comfortably, then got up and came to see what I had painted. He made a surprised sound, and then laughed delightedly.

“And there’s my cameo,” he said. “I love you.”

“Your cameo?” I was thinking of the brooches with the white raised portraits. Cecily is wearing one in the painting in the front hall of our school. I must have seen it one million times.

“In the film. I always do a cameo.” I must have looked puzzled still, because he explained: “I’m the director. Dane Carmichael.”

“Seriously?” I said. I shook his hand and then looked at my own hand. “I think I got paint on you. I’m Harriet. Harriet Devereux.”

He got one of my rags and wiped the paint off his hand.

“Why seriously?” he said.

“Oh, because you’re so young,” I said, hoping I wasn’t being rude. “I thought you were another P.A.”

“It’s my boyish charm,” Dane said. He didn’t look offended at all. “You’re the girl from Maine?”

“That’s me,” I said. I started imagining the silent wrath of Alice in the distance, so I signed the painting and began wiping my brushes.

“I’m interested in shooting up there next. This is a terrible city. What’s it like there? Tell me everything.”

“Oh, God, it’s the best place in the world. Well, except for nine months of winter and terrible bugs the rest of the time.”

I told him all about Maine, except after a while I realized I was just talking about the grounds of Thrushcross, describing it like it was my long lost best beloved. I missed it so much, it hurt. I pressed a hand to my chest, then looked down and saw the inevitable blotch of paint on my shirt.

“You’ll never get away with a crime if you leave paint everywhere you go,” he said, and helped me hang the painting. It looked exactly right there, just as I’d planned, though I’d have to bring a frame for it tomorrow. I congratulated myself silently and packed up all my stuff.

Dane picked up half it to help me carry it, but then led me through the rest of the sets to show me everything.

“Don’t tell these people, but I’d rather be in a real house, under real sky.” He looked at the ranks of lights over the house exterior set, a house that looked exactly like the little one Trevor had been building. “You just moved here, yes?” I nodded. “Don’t let them get to you. They’ll suck the life out of you and take everything you love and ruin it.”

“Okay,” I said. That surprised me, it was so grim, coming from someone who worked in the business.

“But you must love film, if you’re working here,” he said. He looked away. “I’m probably talking to a brick wall.”

“No, I’m just a painter,” I said. “Art department seemed like my thing, like it would be fun. Making artificial worlds, you know?”

He was looking at me intensely again. The thing is, when a guy who’s older and in a position of power keeps staring like that, it generally means he’s interested in something other than conversation. I was starting to get a little uncomfortable, even though he seemed entirely unthreatening and there were a dozen burly set builders who knew me and liked me within easy yelling distance. But still. He seemed to know what I was thinking, though, which made me like him even more.

“I know your aunt,” he said abruptly. “Martha Gilmartin, right? We’ve worked together. She can tell you I’m all right. I don’t chase art department PAs or makeup girls or anyone. They chase me. I just want to learn about Maine. And I like you. All right?”

“Oh, good,” I said. “Thanks for clearing that up. Are you psychic?”

“I read people very well,” he said. “It’s not always pleasant.”

I laughed.

“I always thought being able to read minds would be a curse,” I said. “I know way too much about what people are thinking for comfort already.”

“Yes,” he said excitedly. “You get it. I wish I had some way to shut it off.”

“You had a rough childhood?” I said.

Dane got very still.

“How did you know that?”

“It’s how you turn into a face watcher,” I said. “When you’re around unpredictable or volatile people. I had the same thing. It’s what makes us kind of psychic.”

He folded his arms and stared off at the set for a while. And then, without looking at me, he said:

“Can I buy you coffee?”

“Sure,” I said, surprised.